Nathan Mossell

Nathan Mossell was the first African American to graduate from the University of Pennsylvania’s medical school. His file at the University of Pennsylvania archives center is extensive partly because of his family’s history at the University. His brother was the first African American to graduate from Penn law. A niece, Sadie Mossell Alexander, later attended the same law school and was the first woman to graduate. His file presented a guide to what it was like for a black medical student.

Dr. Mossell enrolled in medical school in 1879 after completing his undergraduate education at Lincoln University (Mossell). According to his papers in his archives file, at the start of his first Penn course, he received a mixed response. He was called racial epithets but also defended by some fellow students against such attacks. Mossell revealed that he was met with a standing ovation at his graduation in 1882. He went on to open Philadelphia’s first black medical facility for black patients, Frederick Douglass Memorial Hospital (Mossell). What was significant about this was that these papers were authored by Mossell. This marked a turn to an approach in research and methodology closer to that of Marisa Fuentes in her recent work Dispossessed Lives. In her book, Fuentes explores the unexplored lives of enslaved women by using records to give a “crucial glimpse into lives lived under the domination of slavery” (Fuentes). Mossell was not writing about slavery, but institutional racism.

Unlike other archival documents, Nathan Mossell’s were in the first person and authored by an African American from Penn. These papers offered a glimpse into black Penn even before his own time in the Medical School. Towards the end of his autobiography, he mentioned a “Dr. Wilson” who gained a medical education at Penn while working as a janitor.

A janitor’s job in the 19th century included cleaning duties as well as collecting class tuition and assisting professors with different odd jobs. Mossell describes “Dr. Wilson” as a “favorite of the University Staff, for he was permitted to attend lecture.” Mossell also claimed to “examine a number of his prescriptions at Procter’s Drug Store at Ninth and Lombard Streets” in what was then known as the 7th Ward, the location of one of Philadelphia’s historic black communities. Mossell claimed that Wilson’s work included excellent “penmanship and orthography.” Files at the University Archives identified Wilson as the man also known to be a janitor at Penn, Albert Monroe Wilson.

~ Research conducted by Bryan Anderson-Wooten

Albert Monroe Wilson

Albert Monroe Wilson first appeared in Penn’s Philomathean Society records incorrectly as “Alfred Wilson.” He is described as the “young colored boy” who assisted Penn janitor Major Dick with maintenance work for the school. However, as time went on Alfred Wilson garnered respect. The Philomathean Society’s records state that Wilson went through a metamorphosis. He went from being described “as a source of worriment and anxiety” to winning the “respect and admiration” of the society “as the years passed away.” This change in attitude can be seen in the Society’s historical minutes. Wilson went from being referred to as “Dick’s Boy”, to “Alfred” or “Alfred Wilson”, and then “Mr. Alfred Wilson.” By the time of his death, he was affectionately known as “Pomp” and had at one time been nominated for membership into the Philomathean Society.

Alfred Wilson’s file stated that he had ceased any form of formal education after being hit in the head with an object during a brawl at the age of 9. Furthermore, it turned out that Albert Wilson served as a janitor at the time Mossell attended Penn. This was impossible to reconcile with Mossell’s account that Dr. Wilson had died before Mossell could meet him. Additionally, it seems that Mossell believed that “Dr. Wilson” worked as a janitor only at the 9th and Market campus site, but Albert Wilson worked at both the 9th and Market location and the new West Philadelphia campus. Finally, Albert Wilson is listed in the archives as primarily aiding professors in the college. For example, there is evidence that he frequently helped physics Professor Henry Morton in his laboratory. The only time he is definitively mentioned in connection with the Medical School is during his time at the Hall Surgeon on 5th street. Even in that capacity, he is a laborer who slept on campus because of his long and tedious work there. After further discussion with Mark Lloyd, I concluded that Mossell’s “Dr. Wilson” was not Albert “Pomp” Wilson.

A careful reading of Mossell’s biography and closer examination of Albert Wilson’s file revealed several discrepancies. University Archives records incorrectly identified Albert Wilson as the “Dr. Wilson” Dr. Mossell wrote about in his autobiography. Bryan Anderson-Wooten worked to correct this archival mistake and conducted research to distinguish the two Wilsons. Learn more about his process and his findings here.

~ Research conducted by Bryan Anderson-Wooten

Dr. James Henry Wilson

James Henry Wilson is significant because his biography reveals how the archives can erase the stories of African Americans. This discovery illustrates how examining historical records using alternative methodologies can unearth previously unknown historical truths.

Wilson’s 1865 obituary from an African Methodist Episcopal Church newspaper, The Christian Recorder. The excerpt below illustrates that this Dr. Wilson had studied at numerous schools during the 1840s in an attempt to obtain a degree to practice medicine. He preferred to do this alone without the available financial resources of his parents. Instead, he gained employment as a janitor. In between work he participated in medical courses.

“Nothing daunted, he, like Peter of Russia, even though his father was comparatively wealthy, hired himself at the Academy of Natural Sciences-then in the College of Pharmacy-diligently applying himself to lectures and books at his command. From this institution, he passed, in the same capacity, to the Jefferson Medical College, and afterwards to the Medical Department of that ancient seat of learning, the University of Pennsylvania“

– Obituary of James Henry Wilson, Christian Recorder, 1865

Unfortunately, like the “Dr. Wilson” in Mossell’s autobiography, James Henry Wilson was not granted a degree from any of these colleges (Weaver). The obituary provides further evidence of the discrepancies between Albert Wilson and Mossell’s “Dr. Wilson.” For example, a young James Henry Wilson is depicted as a “bright lad” and “head of his class (Weaver).” Even after he failed to gain a degree, he went on to open a business with Dr. David Peck, the first African American to graduate from medical school. Consistent with Mossell’s autobiography, James is referred to as “Dr. Wilson.” His obituary stated that even without a degree “some of our most prominent physicians, as Pennypacker, Ludlow, Smith, Bolder, Carson, Allen, and many others, freely consulted with Dr. Wilson, knowing, as we have said, his ability, and knowing also, that he was cheated out of his diploma.”

By referring to James Henry Wilson as “Dr, Wilson,” Mossell was purposefully using a “methodology that purposely subverts the overdetermining power of” erasure in the archives. Instead of writing specifically about the talented all-white faculty from his alma mater, he incorporated medical professionals in the black community that wouldn’t normally receive praise from a Penn medical graduate. His autography doubled as an unofficial memorial for black doctors that pathed the way for his accomplishments.

~Research Conducted by Bryan Anderson-Wooten

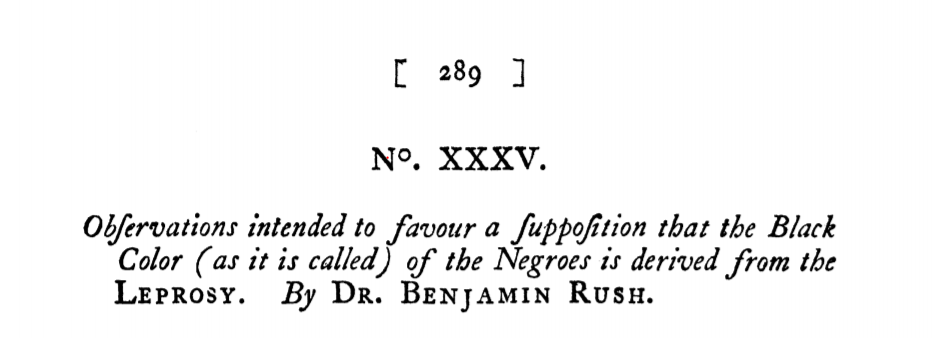

Dr. Benjamin Rush

In 1799, Benjamin Rush wrote an article called “Observations to favor a supposition that the black color (as it is called) of the negroes is derived from the leprosy,” in which he argues that the skin color of black people is caused by disease—specifically leprosy. In this paper, he writes that blackness can be “cured” and that white skin is a healthy state. While this article is well-known by historians it is not well known that he taught this idea to students.

While attending the University of Pennsylvania, Robert Hare was a student of Benjamin Rush. His course notebook, preserved in the University Archives, contains lecture notes from Rush’s course. In the 1796-97 school year, Rush delivered several lectures about racial differences. He is quoted to have said that, ‘Contagions sometimes affect people only of particular nations sometimes those only of a certain colour,’ and that ‘skulls differ materially in different nations.’ The most notable lecture from Hare’s notebook was delivered on January 12, 1797.

This lecture, dedicated to teaching his theory about blackness resulting from leprosy, happened two years before the paper was published. Some of the most problematic elements of his 1799 paper are recorded in Hare’s notebook, written in 1797. This includes the idea that black people are less sensitive to pain than white people and that interracial marriages make white women’s skin color change.

This discovery shows that as a doctor, Benjamin Rush published medical articles with ideas about race that were harmful to black people, and as a professor, he actively taught these ideas to students. He taught Samuel Poultney about yellow fever in 1786 and he taught Robert Hare about leprosy over a decade later. These students and many others would go on to become the nation’s doctors and spread and certify these ideas. It should be noted that he was teaching his theories about blackness resulting from leprosy a full two years before publishing an article on the subject. These lecture notes prove that this was not a hypothesis he developed as a one-off. Not only did he formulate it in his mind for several years, but he had so much confidence in his conclusion that he taught it to his students. His ideology demonstrates the ways in which Dr. Rush can be considered environmental (he believed race resulted from the environment as opposed to races having different origins). These explanations on supposed differences between races gave rise to his students’ ideas on racial differences, including polygenesis, the idea that each race was created differently.

—

Rush’s theories tie back to P&SP’s focus on complicity. Even Rush, one of the “good” intellectuals, who served as the president of the abolition society furthered harmful ideas about race. He taught medical students who would later become doctors and medical lecturers that there were differences between the races. He left the door wide open for later racial pseudoscience that directly contributed to the justification of slavery in the United States. Rush’s work points to the pervasiveness of racism and slavery in early American society. And even a leading intellectual who is lauded as a progressive abolitionist furthered racist ideology and laid the foundation for racial pseudoscience at Penn’s medical school.

~Research conducted by Brooke Krancer. See Brooke Krancer’s previous research on Benjamin Rush. Her research serves as additional evidence that Dr. Rush laid the ideological foundation for the race-based science that would become prevalent in Penn’s medical curriculum in later years.