New Georgia Encyclopedia

George Whitefield (pronounced Wit-feeld) is one of the founders of Methodism and a major figure in the transatlantic religious revivals of the eighteenth century, known as the “Great Awakening”. Whitefield’s major contribution to the University of Pennsylvania was the building on 4th & Arch Street originally intended for his church in Philadelphia, that became the College of Philadelphia’s first campus. He abandoned that building to found an orphanage in Georgia. Established as a proprietary colony in 1733, Georgia initially prohibited slavery. Whitefield was instrumental in advocating for the legalization of slavery in Georgia.

– George Whitefield, ‘Letter to the Inhabitants of Maryland, Virginia, North and South Carolina concerning their Negroes’

Whitefield’s ministry was an inclusive one that embraced the opportunity to evangelize African Americans. In 1740, he published an open letter to the “Inhabitants of Maryland, Virginia, North and South Carolina concerning their Negroes” in the Pennsylvania Gazette. In this letter, Whitefield chastised enslavers for mistreating their laborers. But a closer look at the letter reveals that he never condemned the institution itself, focusing instead on converting enslaved people to Christianity. That same year, he founded “Bethesda,” an orphanage in Georgia, where slave labor had been outlawed 5 years earlier.

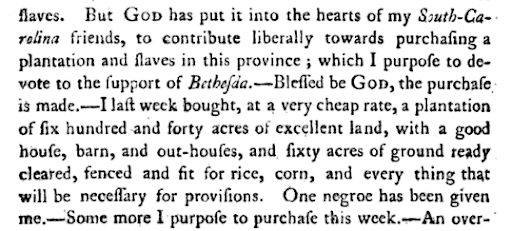

Whitefield soon warmed to slavery. In 1741, upon realizing the difficulties of maintaining the institution and its lands, Whitefield wrote An Account of the Orphan House in Georgia expressing his desire to turn to slave labor. “As for manuring more land than the hired servants and great boys can manage,” he admitted, “it is impracticable without a few negroes.” His new interest in slavery became more apparent in a 1747 letter to “a generous benefactor unknown” in which he claimed, “God has put into the hearts of my South Carolina friends, to contribute liberally towards purchasing a plantation and slaves in this province which I purpose to devote to the support of Bethesda… One negroe has been given me- Some more I purpose to purchase this week.”

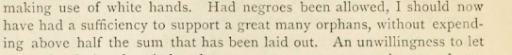

As the orphanage continued to struggle financially, Whitefield continued to think that slave labor could be the remedy for his woes. In 1747, he began to lobby in earnest to legalize slavery in the Georgia colony on the grounds that slavery would benefit, not only the Bethesda orphanage but the entire colony. “The constitution of that colony [Georgia] is very bad, and it is impossible for the inhabitants to subsist without the use of slaves,” he complained. “Had negroes been allowed,” he observed to the trustees of the colony, “I should now have had a sufficiency to support a great many orphans.” He claimed that both his orphanage and Georgia would fail without the institution of slavery.

He gave the trustees an ultimatum, threatening, “I cannot promise to… cultivate the plantation in any manner” if the laws prohibiting slavery were not overturned. The trustees were convinced and in 1752, when Georgia became a royal colony, slavery became the law of the land. Upon his death in 1770, Whitefield bequeathed 4,000 acres of land in Georgia and 50 slaves to the Countess of Huntingdon.

In 1919 a George Whitefield statue was dedicated at the University of Pennsylvania. In 2020 the University of Pennsylvania announced plans to remove the statue.

Stands in Fisher Hassenfield in front of Morris (named after Robert Morris)